There are films whose universal critical approval can only be explained with the stifling power of canonical thinking. A given work is regarded a masterpiece on the basis of a claim which has been uttered a sufficient number of times to sink into popular consciousness and start existing as received truth, multiplying itself ad infinitum. That is what seems to be the case with the most recent opus of Alfonso Cuarón, Roma. As it has been, as well, with a substantial part of his Italian masters’ (particularly Fellini’s and Antonioni’s) prolific output, to which he clearly and profusely alludes in his newest picture. Sounds outrageous? It may be time to openly admit that emperors have often been seen naked.

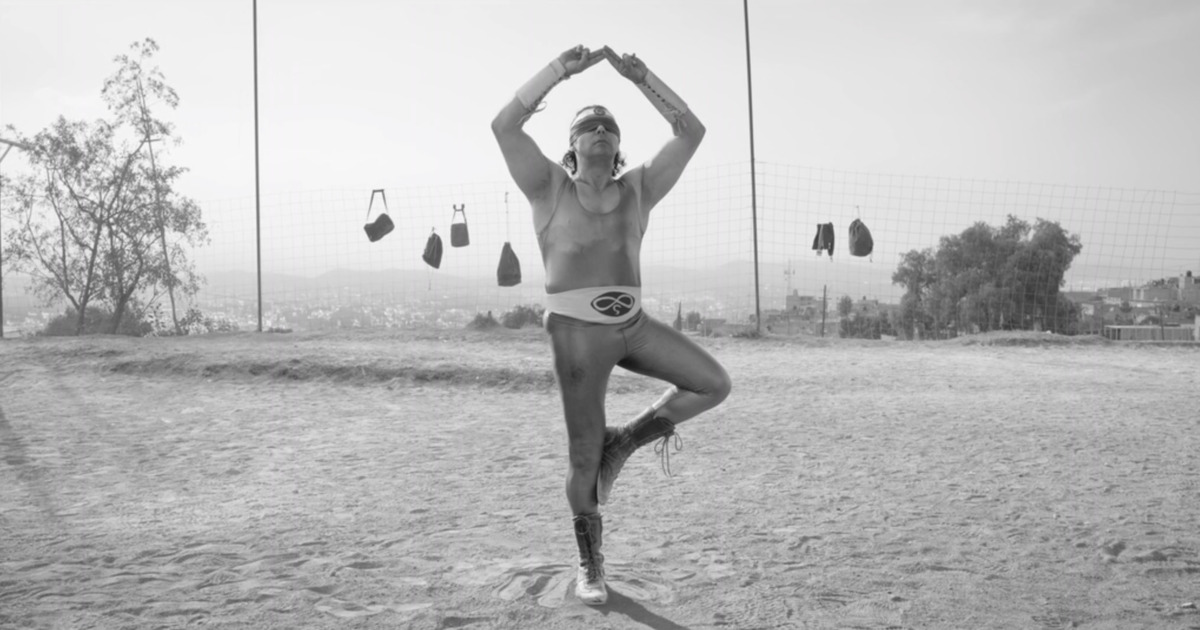

Roma shines with an enticing glow of a self-absorbed beauty. It is easy on the eye but ultimately unfulfilling. Each painstakingly researched and meticulously composed black-and-white shot, executed and edited by the director himself with the use of state of the art digital technology, could easily compete for the World Press Photo awards. As a matter of fact, many of those flawless, painterly images bring associations with the urban chapter of the world-famous photographer Sebastião Salgado’s body of work. However exquisite in every detail of their static presence, in film they blow cold air and fall flat. Turned into an endmost goal, Roma‘s visual perfection lacks genuine sentiment and, thus, real expressive power. Ironically, any emotional impact the picture manages to exert stems from the narrative development and actors’ performances, rather than the imagery itself, leaving the medium’s immense potential frustratingly unsatisfied.

To be clear, the narrative itself, however sporadically effective in conveying the protagonist’s personal drama, hangs on a very thin thread. A semi-autobiographical story about a domestic worker, presented on the backdrop of a Mexican family life, is as sketchy as it can get. Characters are shadow puppets without distinct personalities. The mother (Marina de Tavira) may be seen as an exception in her grotesquely hysterical attitudes, yet her traits are more of a cultural mark than a sign of true individuality. Consequently, Roma resembles a comic book. Relationships are based on societal conventions of class and status. The lead (debutante Yalitza Aparicio) is a patchwork of stereotypes: maid of a peasant background, caring nature and not too brisk mind. She gets pregnant with an arrogant paramilitary thug, who – predictably enough – washes his hands of responsibility. The family she works for, well-off and educated, is dull and shallow, featuring quarrelsome children and their painfully mediocre father, a doctor in the municipal hospital, who ends up running away with a younger lover. Fellini-esque touches of absurd, tearing the fabric of this depressively mundane reality symbolised with dog poo piling on the driveway, are obviously derivative and ultimately meaningless – a mere stylistic gesture of directorial self-indulgence.

The film, whose title most literally refers to a neighbourhood of Mexico City and, somewhat less directly, to the Italian post-war filmic heritage, bringing to mind Fellini’s Roma (1972) or Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945), is allegedly of a very personal kind, having its origin in the director’s childhood memories of a beloved nanny. Yet, it is somehow short of any authentic feeling or atmosphere, usually stemming from an artist’s strong attachment to the subject matter. By depriving his character of individual features, Cuarón makes Cleo a symbolical figure of her class and gender, a martyr of the unjust society. Indignant in his self-righteousness, he seems to have his heart in the right place, but his film, in its clearly feminist and socialist expression, comes closer to a political manifesto than true cinema. In the process of imbuing Roma with his undoubtedly virtuous convictions, he has lost the sense of both nuance and substance and, as a result, the whole creative purpose of his endeavour.

The question about the point behind Cuarón’s latest effort keeps recurring long after the screening of Roma has ended. This tastefully made filmic tableau of the social order in 1970s Mexico is superficial and lacking in deeper intent. It may be due to the fact that its director is much more interested in showing how things appear than what those appearances communicate. Rather than a meaningful cinematic reflection of the surrounding world, Roma can be seen as Cuarón’s love letter to himself. And it is precisely in this self-congratulatory spirit that it reveals its high affinity with some of the neo-realist legacy. Just as Antonioni in L’avventura and Fellini in Dolce Vita, he is splendid at depicting immanently somber aspects of the human condition in a visually astounding form, without ever attempting to peek under the surface of matters. In presenting the world just as it is, in his wide-angled, pristinely sterile takes, Cuarón’s work is not only aimless and inconsequential, but, perhaps even worse, it leaves a bitter aftertaste of guise and pretence.

“This is the first film I tried to do without any sense of influence, and the first film [in which] I consciously tried not to pay homage or do anything derivative.” – Cuarón said in a Guardian interview. “Probably, I’m too much of a cinephile to be an auteur.” – he then added. It may very well be true, as – despite his declarations – Roma reveals a whole range of influences. Antonioni’s ennui seamlessly blends in the film with Fellini’s circus aesthetic and Ken Loach’s political consciousness. There would be nothing wrong with it per se, if those inspirations, once combined, amounted to any real significance. Sadly, it is not the case with Roma. In 1960, cataloguing symptoms of existential malaise, while insistently avoiding adherence to conventional narrative patterns, must have appeared truly groundbreaking. In 2018, however, pointing at life with a knowing smirk and saying “That’s how it is!” seems somewhat lazy. And this is the crucial reason why Roma, as impressive as it looks on the outside, feels so hopelessly empty on the inside.

©AB, Tracks & Frames, 2019

English

English polski

polski português

português