Existential vacuum is a subject that hits home with many film directors of the now quickly maturing generation X. Their interest in the age-old phenomenon, which tends to gain importance each time society goes through a period of accelerated technological growth, however unsurprising, is highly commendable, as it allows us to take another look, with the aid of the hyper-perceptive camera eye, at the ever vulnerable yet essentially unchanging human condition. Bart Layton, British documentarian acclaimed for the TV doc series Banged Up Abroad and the full-length film The Imposter, knows better than most how to employ the tool for investigative purposes. In his newest work, American Animals, he sets out on a cinematic venture involving both facts and fiction, and comes up with (excuse the pun) truly unreal results.

“This is not based on a true story” – we are dutifully informed upon embarking on this cinematic journey into the unknown. “This is (…) a true story” – the previous statement morphs in front of our very eyes, instantly questioning the viewers’ assumptions acquired as a result of their long-term exposure to popular culture. It is a crucial gesture, as it reveals the principles of the game we are about to play. Having uncertainty for its driving force, the narrative fiddles with senses, disputes memories and conjures impressions not only of the spectators but, more importantly, of its own protagonists, both on screen and in the so-called real world, where the events in question have originally unfolded.

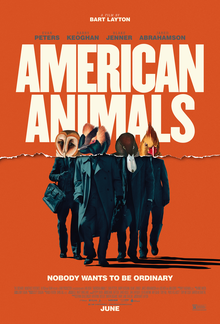

In 2004, four men in their early twenties, including two students of Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, performed a heist of the School’s library containing extremely rare books, such as John James Audubon’s Birds of America and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Driven by boredom and hunger for excitement, the young perpetrators, enthralled by the plots of famous genre movies, such as Kubrick’s The Killing and Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, devised a largely impractical plan of action and heavily failed in confrontation with reality, ending up sentenced to seven years in a federal prison.

It is precisely the sharp contrast between the prosaic nature of real crime experience and the sleek world of cinematic villainy that lies at the very core of the film’s appeal. Well versed in the realm of facts, Layton makes a bold move of blending the two worlds into one. He achieves it by interviewing the now repented robbers and their families and alternating bits of their account with a filmic re-enactment of the reported events. Constantly switching between different points of view, the narrative unfolding on screen at once mirrors, completes and challenges the real men’s comically contradictory statements. Intentionally inconsistent and self-referential, it is revelatory of the volatile nature of memory and individuality of perception. The ambiguous picture of the past resulting from this highly creative process of cinematic deconstruction serves as an incentive for a deeper reflection on the nature of fact and subjectivity of truth.

An intriguing meta-commentary on the substance of time and the mysterious ways in which our brains deal with visual data both in life and in film, American Animals provides, as well, a compelling diagnosis of the societal status quo. The film’s protagonists belong to the suburban American middle class. Although their family lives don’t always follow the prescribed ideal, none of the young men suffers from any kind of social pathology. Quite the contrary – all four are financially comfortable and one could even be regarded as exceptionally privileged. They do, however, suffer from the complex of provinciality, disillusion and insatiable thirst for novelty. The small town reality, where the only option of entertainment, beyond drinking in a bar, is setting a supermarket trolley on fire and watching it speed through a parking lot, frustrates them to the point of desperation. In search for an intangible thrill, they put all their energy into devising a heist plan. Peer pressure, urge to prove oneself and one’s masculinity, along with a typically unjustified conviction of own uniqueness (an undesired side effect of indulgent parenting) equally contribute to the final disaster.

Despite a recurring inner voice of common sense, Spencer Reinhardt (Barry Keoghan), a promising art student with a supportive home and all conditions to find fulfilment in his adult life, succumbs to the persuasive powers of a little less fortunate and somewhat more frustrated friend Warren Lipka (Evan Peters). Victim of a parental projection, Warren pursues his athletic education for no other reason than to please his father. An avid film viewer with a substantial DVD collection, he is determined to add some spice to his, as he perceives it, utterly dull existence. The pair co-opt two childhood friends, Erik Borsuk (Jared Abrahamson), a geeky economics student, and Chas Allen (a well-off young entrepreneur) to help the logistics of their plan. While Erik joins in order to regain Warren’s friendship, the more down-to-earth Chas is lured by the perspective of an easy gain.

Regardless of their different motivations and varying degrees of doubt, the four men’s decision to go ahead with the idea points just as much to their juvenile naivety as to the serious crisis of values permeating modern society. As the ineffectively “neutralised” librarian Betty Jean Gooch would have it, the ideal of self-affirmation through use of one’s talents and skills to own and others’ avail has perished, and no other principles seem to offer enough appeal to serve as valid substitutes. In the age of short attention spans and desire for immediate gratification, ambition and dedication appear as tedious and archaic as a steam train, while the need to break out from the old-fashioned standards grows in proportion to the quickly accelerating pace of life.

However mindful of the medium’s delusory power, Layton’s opus remains a highly entertaining piece of action cinema. Never falling into the trap of the vérité convention employed by the majority of his British counterparts in both documentary and fiction films, the cinematographer Ole Bratt Birkeland creates the suspended sense of realism with a masterly application of diffused light, from both natural and artificial sources. His work is aided by an excellent editorial team seamlessly transitioning from the real-life subject to the fictionalised enactment and making an intelligent use of documentary techniques, such as rewinds and frozen frames, for the purpose of illustrating flawed mechanisms of human memory. Collectively, they succeed at building and maintaining visual attraction from the beginning to the very end of the relatively complex narrative. Finally, the entrancing string-based sonic landscape composed by Anne Nikitin perfectly enhances the film’s dynamics of intense, adrenaline-fuelled action and nuanced reflection.

All in all, it should be said that American Animals‘ biggest strength lies in the director’s evident concern with the flux of time and, even more importantly, the virtually imperceptible moment which marks the point of no return. Masterfully conveyed on both the narrative and cinematographic level, it appears as the film’s first principle. Before the point of no return is reached, life is an open book, full of brilliant possibilities ready to explore. Once it has been crossed, all those perspectives suddenly narrow down and crumble into a pile of debris, leaving only a tiny opening at the end of a very long and dark tunnel (provided that the source of light is still present). Bart Layton expresses this trivial truth in the most intriguing of ways – by turning the medium, whose very constitution makes it an ideal choice for the purpose of preserving and analysing time, right upon itself. A film in a film, American Animals is a meditation on the content of a human mind becoming the fabric of life and vice versa. Frozen image, moving image, flicker of colour and flutter of sound – all those traces of a passing instant form the substance of the stories we live, both on screen and in our dreams, while awake or asleep.

In the final sequence of the film the real Spencer walks out of his house in order to pick up a newspaper and catches a glimpse of a car carrying his younger self and his mates to the scene of crime. Sometime in the middle of the film, we observe the same moment from the inverted perspective, that is through the eyes of Barry Keoghan, the actor brilliantly impersonating Spencer, cold sweating in the vehicle, as it moves towards his character’s still undetermined future. This single scene exudes the very essence of cinema. The magic of a split second captured and fixed on our retina for as long as we are alive.

©Anna Bajor, Tracks & Frames, 2018

English

English polski

polski português

português