As the long wait for the European release of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin is coming to an end, the London audiences’ appetites have been whetted by the fascinating retrospective of the acclaimed Taiwanese director’s oeuvre held at the BFI Southbank this past September. Special attention was given to the 1995 picture Three Times, whose extended run allowed anyone not yet acquainted with Hou’s original aesthetic to get an all-telling glimpse into the director’s cinematic world.

A film of rare, fleeting beauty, Three Times unfolds slowly, like an ancient Asian scroll, gradually revealing to the viewer its impressive glory and wealth of meaning. Composed of three love stories featuring the same acting pair of Shu Qi and Chang Chen, yet set in three different eras of Taiwan’s history, Hou’s film captures the essence of the deepest human emotion in the changing landscape of societal norms and customs.

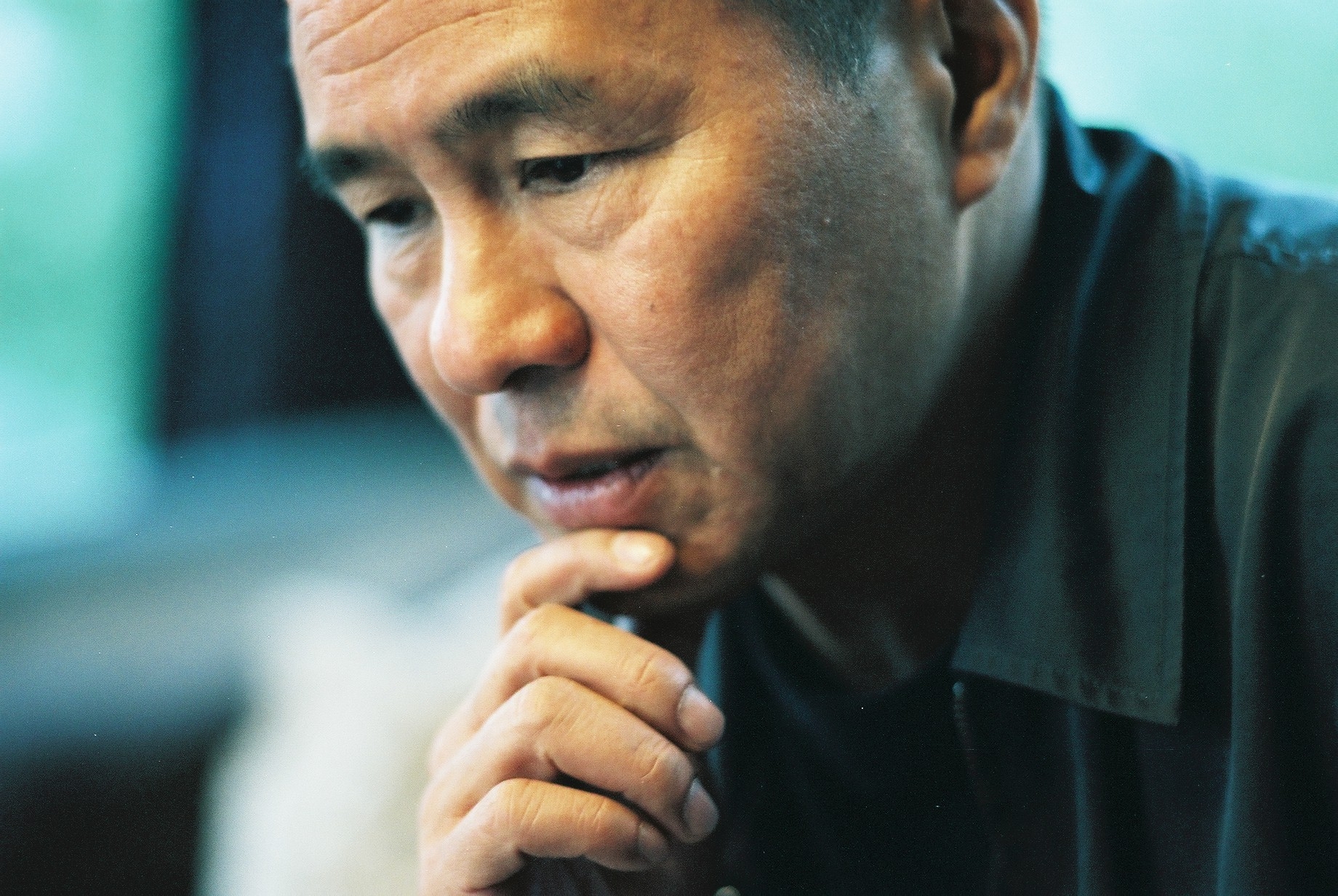

Since his first independent work as a co-director of The Sandwich Man, time has been at the centre of Hou’s cinematic vision. He allows it to flow naturally, allowing the viewer to take delight in the unique flavour of each passing second. His predilection for long, wide-angle shots gives his films a special meditative quality, which influences the spectator’s perception of the surrounding world long after the screening has ended. Once you get caught in the spell, there is no escape from Hou’s magic. Three Times is one of its finest examples.

The film’s opening chapter, A Time for Love, takes place in the Taiwanese provinces of 1966. Having received army call-up notice, Chen says goodbye to the snooker-hall girl he has been pursuing in a heartfelt letter rich in contemporary musical references. Soon, while on leave, he visits the town only to discover that the object of his desire has moved out and her position has since been filled. Initially reticent, he finds himself deeply attracted to the new girl named May, who seems to reciprocate his feelings. And although for a brief moment he loses track of her too, this time the mutual attraction is strong enough to overcome any obstacles.

In someone else’s hands this simple storyline could easily turn into a sugary disaster. With Hou at the command it is a showcase of artistic sensibility. The first thing that comes to the viewer’s attention is the perfectly balanced frame achieved by Hou’s favourite cinematographer Mark Lee (Ping-bing). The camera fixed in the centre of the room scans the characters’ movements while they engage in a billiard game which soon evolves into a courting ritual. It all happens in small gestures, side glances and faint smiles lurking in the corners of lips. Brilliantly led by the director, the two actors rise to the top of their game.

May starts her day by opening the hall’s sliding door to let the mellow daylight in. Then she proceeds to clean and prepare the table. When the darkness falls and electric lights are switched on, the room’s echoing silence evolves into the rustle of soft conversation punctuated with a rhythmical rattle of snooker balls. This subdued soundscape is wonderfully complemented with diegetic and non-diegetic music which can be seen as one of the film’s leading characters. The opening radio broadcast of Smoke Gets in Your Eyes sets a tone for the whole narrative. As it slowly unfolds, the director repeatedly cues Aphrodite’s Child’s song “Rain and Tears”, which eventually comes into prominence in the chapter’s final sequence, culminating with the two meant-to-be lovers waiting in a downpour for a bus that is supposed to take Chen back to the army camp. The impressive poignancy of this scene alone, achieved with the subtlest of means, would be sufficient to justify Hou’s status as one of modern cinema’s greatest poets. Everything from the oneirically green palette through to the light and the music is worked out to an utter perfection in order to create a unique mood of appreciation for life, independent of the joy or sorrow it brings – an approach which is fundamental to Hou’s artistic philosophy.

The film’s second section, A Time for Freedom, transports the viewer to the Japan-ruled Taiwan of 1911. Set in a luxurious brothel, the story – whose dominant tones are purple and brown – focuses on the relationship between a beautiful and nameless courtesan and her young republican visitor, Mr. Chang. By adopting the silent film convention, Hou enhances the parlour’s secretive atmosphere as well as the distinct elegance of the era’s customs and attire. The subtle glow of light seeping through the partly open shutters underlines the texture of fabric so suggestively that, despite the absence of sound, we can nearly hear the discreet rustle of silk accompanying the characters’ movements. The director breaks the silent film convention only in a few instances when the courtesan plays lute and sings a premonitory song about loss. Otherwise, an expressionist piano serves as the only audio commentary to her personal tragedy, which, interestingly, mirrors the destiny of Taiwan abandoned by the mainland republicans in its fight for independence.

The grimmest of the three, the film’s final chapter, A Time for Youth, features a cold, grey-and-blue palette and an urban cacophony, including the rackety noise produced by the protagonists’ preferred means of transport – a motorbike. Taking place in a high density, concrete-built agglomeration of contemporary Taipei, it is a piercing portrayal of the modern man’s way of living and loving based on the example of the bisexual, epileptic pop star Jing, her boyfriend Chen and girlfriend Micky. Rushed and angst-ridden, the characters lead a mostly nocturnal, alcohol-fuelled existence lit only by colourful club lights and computer screen glow. Love letters, so far functioning as the main channel of communication, have here been substituted with texts and e-mails. Music, presented mostly diegetically as Jing’s artistic output, is computer composed and keyboard executed. And yet – despite all the changes affecting manners, body language, fashion and musical taste – human emotions, however confused, seem timeless. The primordial need to love and to be loved never dies.

As he has clearly demonstrated throughout his filmmaking career with such beguilingly meditative pictures as A Time to Live, A Time To Die, Dust in the Wind and City of Sadness, Hou Hsiao-hsien is fascinated with the pressure that time exerts on a man as an individual and a member of an economically and culturally conditioned society. Here, by correlating elements of three different stories unfolding in three different historical periods, he achieves the effect of fluid continuity whose source seems to lie in his unshaken conviction that our existence, both before and now, reveals itself through emotional bonds we form with other human beings.

©AB, Tracks & Frames, 2015

English

English polski

polski português

português