I must admit I wasn’t immediately inclined to see the newest Christopher Nolan film on the big screen. Not particularly acquainted with the director’s previous work, I almost made up my mind to pass on Interstellar, expecting some kind of overblown, preposterous Hollywood folly addressed to completely undiscerning popular audiences. The sole factor that made me reconsider my decision was Matthew McConaughey playing the leading role. It was the star of Mud and The Dallas Buyers Club, for whom I have a great respect, that opted to participate in this project, so maybe it wasn’t going to be all that hopeless? Chances were that I would miss out on something relevant and then bitterly regret my indifference. So I resolved to give it a go. But that’s not the end of the story… In less than a week I found myself watching it for a second time. And now, writing these very words, I can’t wait to see it once more, this time on a proper IMAX screen. Yes, it is THAT good.

Originally, the script of Interstellar was commissioned to Jonathan Nolan, Christopher’s younger brother, by Steven Spielberg who was supposed to direct the movie for Paramount Pictures. But in 2009, Spielberg and his production firm Dreamworks left Paramount for The Walt Disney Company. In this new scenario, Jonathan recommended Christopher to direct the film. The creator of Inception readily accepted the offer, setting one condition: that he would write his own screenplay and merge into it his brother’s ideas.

Jonathan, who for the purpose of his assignment studied relativity at the Californian Institute of Technology, placed the first half of his story on a resource-depleted Earth of the near future. Christopher kept this concept, introducing just a few minor but highly consequential changes. For instance, Coop’s son Murph became a daughter. This modification, at first glance of lesser importance, added to the script a significant emotional weight, much improving its overall expression. The second part of the text, in which a team of astronauts travels beyond our galaxy, underwent much heavier editing process. Extremely convoluted and containing a plethora of loosely connected motifs, the original story featured Chinese presence in space (which had apparently continued for over 4000 years [sic]), anthropomorphic robots, fractal alien life and zero gravity sex. Christopher trimmed the overinflated material, throwing away some by-products of his brother’s fertile imagination, and drew a relatively coherent plot. Still, he made full use of Jonathan’s best ideas, recycling and implementing them into the previously inexistent context. The resulting screenplay is a consistent and refreshing piece of writing devoid of triviality and cheap tricks commonly found in Hollywood-style filmmaking.

Telling the story of Cooper, a widowed father of two kids and a trained NASA pilot who travels through a wormhole to a distant galaxy in search of a new home for humanity, Interstellar is not just another sci-fi adventure, but an ambitious, intellectually stimulating and emotionally intense film for true lovers of cinema. And that is because, instead of indulging in spectacular visions of extraterrestrial creatures and future advances of technology, it centres on the singularity of human experience.

By magnifying temporal and spatial distance, the grand theme of time travel allows to highlight solitude as an inherent element of life. What’s more, as it naturally entails direct encounter with the immense universe and its irrepressible forces posing imminent danger of death, it tends to expose the most visceral of fears that haunt humanity since the beginning of the world. Thus, it brings to light our innate instinct of survival, the glorious “rage against the dying of the light”. Intensified by the mere thought about our children, for whom we are capable of making just about every conceivable effort to live a little while longer, this powerful drive sets personal interests ahead of the collective good, uncovering our essentially selfish natures. Nonetheless, it is this very same human nature that triggers our ambition to aim farther and higher, “to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars”, “to break barriers (…), to make the unknown known”. And all that in the limited frame of time we are given to our disposal.

*** SPOILER ALLERT***

In Nolan’s wonderfully cinematic tale, McConaughey’s character Coop, having resolved to join the intergalactic mission, painfully parts with his beloved daughter Murph (McKenzie Foy) who desperately tries to divert him from his decision. Unable to estimate the amount of time he is going to spend in space, Cooper jokes they might even be the same age when he is back on Earth. But he promptly regrets his insensitive remark. Heartbroken Murph gives up on convincing her dad to stay and withdraws into herself. Months and years later, travelling through space and watching recorded messages from his family, Coop yearns to hear from his girl whose wounded pride prevents her from reaching out.

While on the planets orbiting the black hole Gargantua time moves slowly, on Earth decades will pass before Murph (played as an adult by Jessica Chastain) decides to break her silence. Having, like her dad, become an engineer and a NASA employee, she is now helping Professor Brand (Michael Caine) to solve a gravity equation which could save humanity from extinction on Earth. Years go by and the dying Professor confesses to Murph that, unable to reconcile the equation with the quantum theory, he had abandoned the original plan of relocating humanity into space long before Coop’s mission took off, which is to imply that the Endurance crew were never expected to come home. Initially shocked and suspecting her father of deliberately leaving her and her brother on Earth to certain death, Murph ultimately comes to grips with her emotions and develops a conviction that the equation could work with additional data from the black hole’s singularity. The solution to the enigma comes as the biggest surprise in one of the most astounding scenes in the history of cinema.

The idea of presenting Murph’s storyline in parallel with dramatic events in outer space brilliantly illustrates the concept of solipsism, that is perception of self as the only valid point of reference, or – to put it differently – assumption that the only reality sure to exist is the reality of our minds. According to this notion, once we are separated from our loved ones, there is no way we could confirm their existence other than looking inward. That is because the only thing that can bring them back to our realm is a true and powerful sentiment. “Love, Tars. Love (…), that’s how we find things here”, says Cooper from the five-dimensional space he finds himself in at the final stage of his journey.

Yet, when he finally reaches home, the world as he had known it has aged 93 years and Murph, although still alive, can only say goodbye to her dearly missed dad before her time comes to an end.

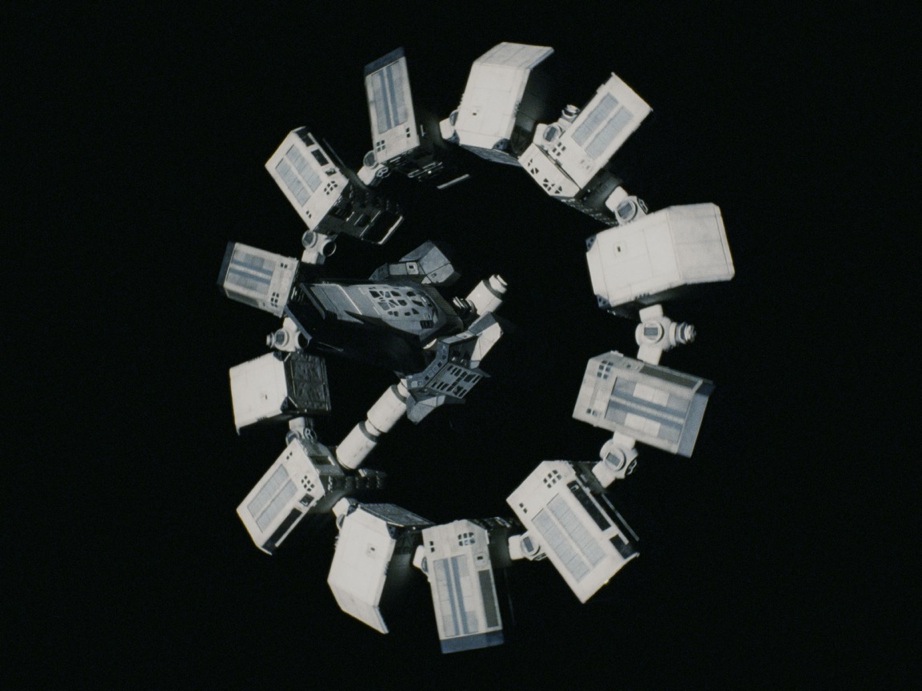

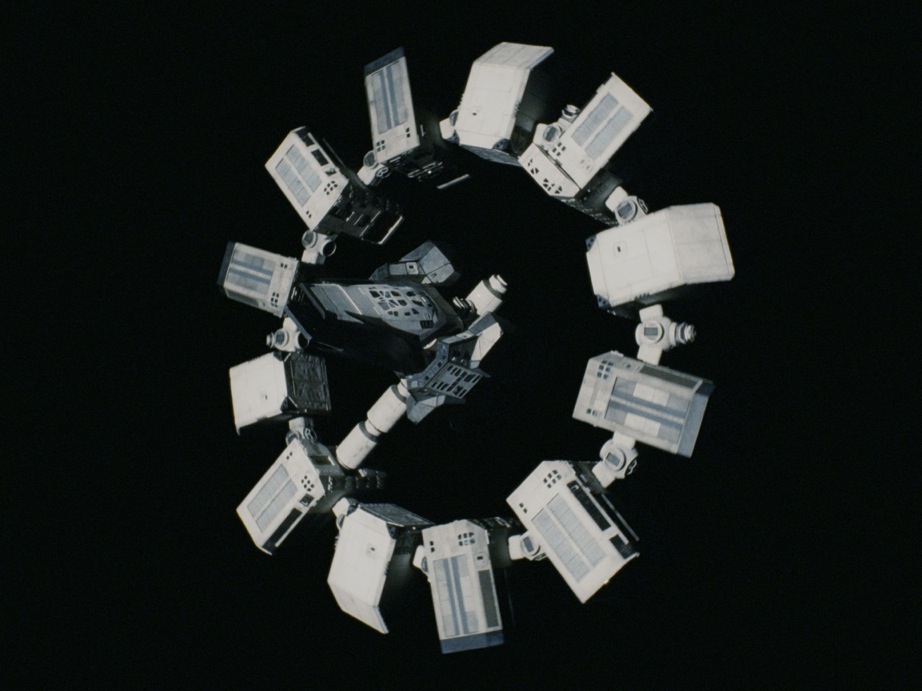

All the above is not to suggest that Nolan’s work is merely an ambitious psychodrama staged on a backdrop of the starry universe. Actually, quite the opposite. As much as the astronautical theme opens way to insightful ontological reflection, the spatial odyssey depicted in Interstellar is of a magnificent value in itself. Wonderfully materialised by Hoyte van Hoytema, a Dutch-Swedish cinematographer educated at the Polish National Film School in Lodz, Poland, Nolan’s vision of cosmos is fascinating to behold. Its sense-assaulting 70mm magnitude contrasts interestingly with the subtle 35 mm portrayal of life on Earth. Maintained in a warm yet slightly faded palette, the intentionally unfocused images of the future agrarian society seem all at once matter-of-fact and unreal, dream-like. This effect is only intensified by open shots of vast corn-fields from above. Their rough, unsettling beauty has an obvious parallel in the breathtaking visuals of space. In characteristic Van Hoytema style though, panoramic views do not tend to overwhelm the narrative, as they are frequently juxtaposed with an amazing wealth of details. To make things even more impressive, this inherently dynamic material is edited with plenty of sharp cuts and accompanied with dazzling, data-rich visual effects by Double Negative.

It’s impossible to think about this picture without hearing its soundtrack play somewhere at the back of one’s mind. Created by the German composer Hans Zimmer, recently known for his work on Inception and 12 Years a Slave, this haunting, monumental and ethereal score is the beating heart of the film, its true soul without which the director’s vision just couldn’t be complete.

The sound mix deserves a separate mention as it has stirred some serious controversy due to the sometimes barely inaudible dialogue. According to the director, however, the blur was intentional: There are particular moments in this film where I decided to use dialogue as a sound effect, so sometimes it’s mixed slightly underneath the other sound effects or in the other sound effects to emphasise how loud the surrounding noise is. It’s not that nobody has ever done these things before, but it’s a little unconventional for a Hollywood movie. It certainly is, as are many other aspects of this outstanding production providing the audience with the most visceral sensory experience possible to imagine.

Beside the enthralling script, stunning cinematography and poignant music, the greatest value of Nolan’s newest work lies in the quality of acting. Matthew McConaughey as a loving father torn between paternal obligation and the passion of a true explorer is no less than remarkable. His marvellously expressive face gives away all the excruciating pain of not being there for his children, the regret of not being able to watch them grow and, most of all, fear of never seeing them again. He is partnered in great style by the newcomer McKenzie Foy portraying the young Murph. Not far behind is Anne Hathaway in the role of Doctor Brand – probably the most interesting performance in her career up to date.

“Our greatest accomplishments cannot be behind us, because our destiny lies above us”, says Cooper in one of his most memorable lines. It certainly reflects the way Christopher Nolan thinks about his craft. Never completely satisfied, he constantly aims higher, and he succeeds. Influenced by Stanley Kubrick’s elliptical masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey and containing a variety of cultural references (the most evident among them being the Borgesian motif of library), Interstellar is a tremendous cinematic achievement and undeniably one of the greatest films ever made. It is also the most plausible in scientific terms, as certified by the renowned theoretical physicist Kip Thorne who made sure the screenplay didn’t venture too far from what is physically conceivable, even if only in the hypothetical realm. At once highly compelling and deeply touching, Interstellar passes the most important test a film can pass: it draws us, the public, into its peculiar world with such an amazing power that we forget it actually is just a… film. And for this very reason we want to watch it over and over again – to live it to the most, absorbing all the flavours and subtleties until they are utterly appropriated and become part of our personal imagery.

©Anna Bajor, Tracks & Frames, 2014

English

English polski

polski português

português