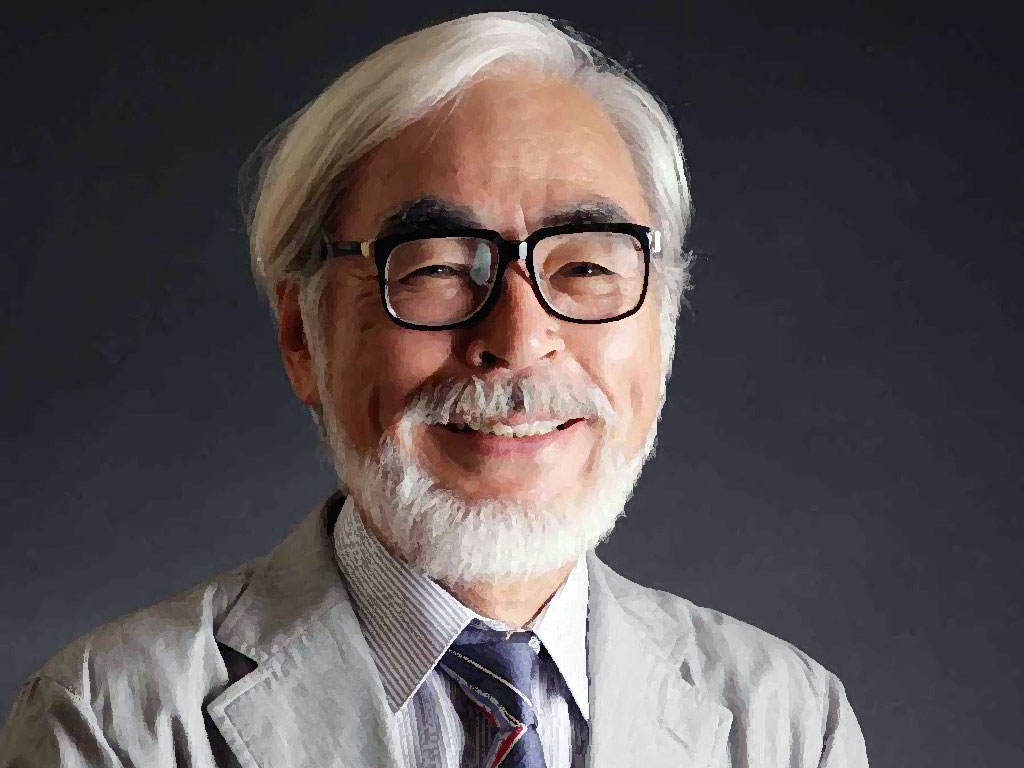

The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, Mami Sunada’s documentary dedicated to Studio Ghibli, the iconic cultural institution of Japan whose cinematic output is admired by diverse audiences all over the world, has just had a limited release at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. And it so happened that the opening coincided with the ceremony of Governors’ Awards in Los Angeles, during which Hayao Miyazaki, co-founder and director of the Studio, received an honorary Oscar for his lifetime achievements in the motion picture industry. To quote John Lasseter, chief creative officer at Walt Disney and Pixar Animation Studios who presented the Oscar to the filmmaker, “Hayao Miyazaki has deeply influenced animation forever, inspiring generations of artists to work in our medium and illuminate its limitless potential. (…) In stature, in influence, in the range and quality of the body of his work, there will never be another to rival him.” Sunada’s film lets us peek through the back door into the world of the Japanese genius of animation. Its narrative presents the daily face of Ghibli, which is the place of work for 400 talented and dedicated people guided by the charismatic, yet unassuming and amiable master.

With eleven full-length features and several short films in his resume, the 73 year-old Miyazaki has created a fascinating imaginative world which proves irresistible to both adults and children. Faithful to the traditional technique of hand-drawing, he meticulously crafts his stories, paying extreme attention to the characters’ facial expression, gait and gesture, as well as to the most minuscule details of their surroundings.

Since the very beginning of his career, Miyazaki’s films have shown the director’s great concern for the environment affected by the progressing trend of globalisation and the insatiable human appetite for natural riches. The animator’s ethical approach towards nature is a logical consequence of his Shintoistic vision of the world, according to which every living creature deserves to be treated with respect. This philosophy extends to work perceived as the main purpose of life and, occasionally, also a source of joy and satisfaction. Hence the imperative of complete dedication to the chosen craft and pursuit of high quality results.

Although highly demanding and even slightly authoritarian towards his employees, Miyazaki appears a very cheerful and kind-hearted person with the most infectious smile. Always polite and considerate, he represents the now almost extinct ideal of a wise mentor who steers his pupils in the right direction, firmly yet respectfully, trusting in their intelligence and good judgement. As one of Ghibli employees says in the film, working for him is a lot more fun than you might imagine. “It’s more like a school. Maybe I shouldn’t say that (laughter).” Although challenging, it seems even more enjoyable and rewarding, if we take into account the perfectly balanced, bright and airy environment of the new premises designed by the master himself, whose aim was to aid concentration and stimulate creativity. With friendly atmosphere and fun routine involving team exercise, it is the exact opposite of the corporate world which Miyazaki has frequently and vehemently criticised.

At the time of the documentary shooting, the Studio was in the very dynamic, final phase of work on two films: Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and Isao Takahata‘s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. While Miyazaki’s picture, based on a fictionalised story of the famous Zero planes’ constructor Jiro Horikoshi, was nearly complete, Takahata’s animation, already almost ten years in the making, seemed to have come to a complete standstill.

Takahata, six years Miyazaki’s senior, does not draw his films and never worked as an animator before becoming a director at Toei Animation, where the two met in 1968 while working together on Hols: Prince of the Sun. By contrast, Miyazaki, having started his career at Toei in 1963 as an in-between-artist, quickly progressed to the position of chief animator, concept artist and scene designer, and soon began co-directing with Takahata. Finally, in 1979, after several workplace changes, he moved to TMS Entertainment subsidiary Telecom Animation Film to direct his first anime feature Castle of Cagliostro. Five years later, in 1984, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the first film both written and directed by Miyazaki, was released. It contained many themes and motifs which were to prove recurrent in Miyazaki’s career: concern for the environment along with passion for flying machines, pacifism, friendship and love. In 1985 Miyazaki, Takahata and Yasuyoshi Tokuma started the animation production company Studio Ghibli with funds of Tokuma Shoten, the publisher who issued Nausicaä in the form of a serialised manga, greatly expanded by Miyazaki over the following decade. Extremely important in this project was Toshio Suzuki, at the time a Tokuma Shoten editor. Using his influences, he helped Nausicaä come to life and soon left the firm to become producer and president of Ghibli.

Laputa: Castle in the Sky, a story of two orphans in search of a magical castle that floats among the clouds, and My Neighbour Totoro, a wonderfully uplifting tale about two young sisters interacting with forest spirits, were the first two animations which Miyazaki realised under the new label. Similarly to Takahata’s beautifully bleak Grave of the Fireflies, animated drama of two siblings desperately struggling for survival during the Second World War, they beat records of popularity to the present day. Since then the Studio released fourteen more animated gems of feature length, including five films by younger directors, such as Yoshifumi Kondo, who debuted with Whisper of the Heart and died three years later as a result of an aneurysm, Hiroyuki Morita, creator of The Cat Returns, Hayao’s son Goro Miyazaki who directed Tales from Earthsea and From Up on Poppy Hill, and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, creator of Arietty. And although not all Ghibli productions are outstanding (Only Yesterday, with its rather ungainly animation, and Tales from Earthsea, famous for its narrative inconsistencies, seem to me the weakest ones), its body of work is characterised by an uncommon artistic and ethical integrity. It is probably a natural consequence of the unusually strong human ties within the company, to which Miyazaki and Suzuki repeatedly refer in the film. For, “without talented people, you can’t make good films. (…) Ultimately, it’s about who you work with. Only those who choose the right people to work with will be able to do the work they want.”

Sunada’s subtle and reflective picture perfectly captures personalities of Miyazaki and his collaborators, as well as the Studio’s creative spirit. It presents to the world the inner workings of the kingdom built on dreams and powered with imagination. Its sovereign, proudly wearing a white apron with an embroidery depicting a family of bears, managed to preserve a child within his grown-up self, and, by means of his work, attempts to persuade his adult audiences to protect their own childish dreams from disappearing. That is not to say he is not fully aware it is becoming an increasingly complicated task. “You know, people who design airplanes and machines… No matter how much they believe that what they do is good, the winds of time eventually turn them into tools of industrial civilisation. It’s never unscathed. They’re cursed dreams. Animation, too. (…) Today, all of humanity’s dreams are cursed somehow. Beautiful yet cursed dreams. I’m not even talking about wanting to be rich or famous. Screw that. That’s just hopeless. What I mean is, how do we know movies are even worthwhile? If you really think about it, is this not just some grand hobby? Maybe there was a time when you could make films that mattered, but now? Most of our world is rubbish. It’s difficult.”

Still, against all the odds, including external pressures the Studio is suffering, Miyazaki and Takahata have succeeded in remaining true to themselves. What about the future? “The future is clear. It’s going to fall apart. I can already see it. What’s the use worrying? It’s inevitable”, flatly states Miyazaki. Having completed The Wind Rises, the project whose progress Sunada’s film diligently documents, he is now officially retired. At the staff screening of his final work, however, he cheerfully declares: “I hope to work for ten more years”. Takahata, on the other hand, despite all the negative rumours, has at last finished The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, whose official Japanese release took place in November 2013. While to the American public the film opened nearly one year later, in October 2014, it is still to make its way to the UK and European cinemas, with the release date so far undisclosed. Based on the 10th century folk story The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, it is told to be the best Takahata’s work to date. Described by “The New York Times” reviewer as “exquisitely drawn with both watercolour delicacy and a brisk sense of line”, it looks like another Ghibli pearl has just been born. And, as it is impossible to predict whether there is more to come, we should enjoy the thrill of expectation while we can.

Let the last word belong to the master himself. Here is Miyazaki-san’s personal dedication to us, the public, and most of all, to the next generation of animators: “Look over there. See that house with all the ivy on it? From that rooftop, what if you leapt onto the next rooftop, dashed over to that blue and green wall, jumped up and climbed up the pipe, ran across the roof and jumped to the next? You can, in animation. If you can walk the cable, you could see the other side. When you look from above, so many things reveal themselves to you. Maybe race along the concrete wall. Suddenly, there in your humdrum town is a magical movie. Isn’t it fun to see things that way? Feels like you could go somewhere far beyond. Maybe you can.”

©AB, Tracks & Frames, 2014

English

English polski

polski português

português