Paul Dano’s directorial debut Wildlife takes its time to grow on the viewer. The initial scenes, suggesting a conventional family drama, seem somewhat unconvincing. There is a sense of tentativeness in the manner the inexperienced helmer/screenwriter handles the story, revealing itself in his excessive reliance on the actors’ input for establishing the filmic narrative. Thus the initial home idyll sequence, rich in gestures of parental encouragement and approval directed at the teenage protagonist, has an artificial ring to it as it tries to make up for the script’s flaws by cramming too much feeling in too little content, putting at risk the viewer’s suspension of disbelief and their further trust in the film’s premise.

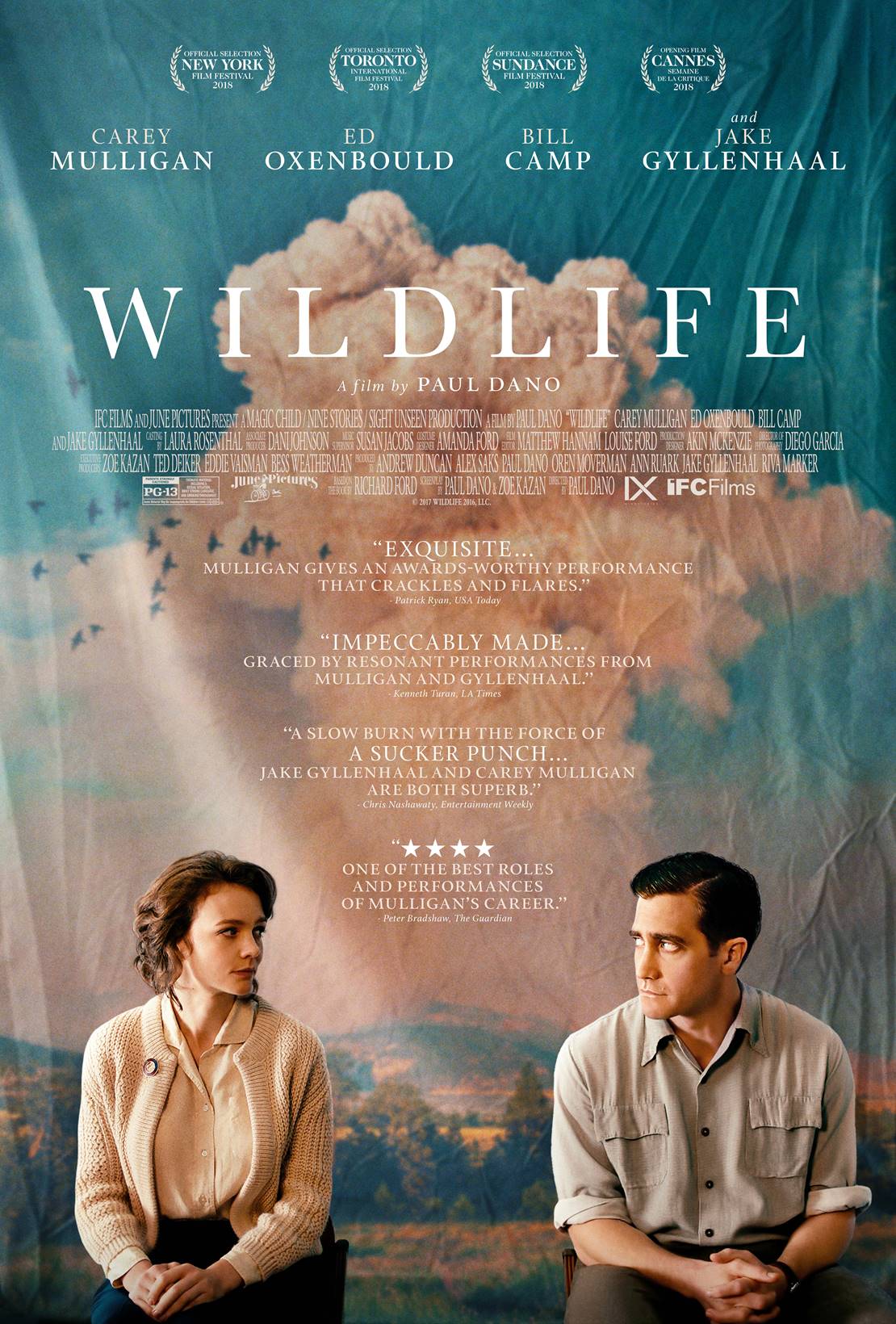

However, once the story gains pace, the writing becomes more and more consistent and false notes less frequent, as Dano allows his actors to focus on developing their characters, rather than on filling narrative gaps. Adapted from Richard Ford’s novel of the same title, the film, co-written by the director and his partner Zoe Kazan, is set in the 1950s’ Montana ravished by seasonal fires. 14-year-old Joe (Ed Oxenbould), the only child of Jeanette (Carey Mulligan) and Jerry (Jake Gyllenhaal), watches his seemingly perfect family life disintegrate, as his father loses his job at a golf club and, instead of looking for another sustainable source of income, first lingers around watching his wife and son take over breadwinning responsibilities, and next resolves to leave home in order to fight the blaze for a minimum pay. His decision triggers a violent reaction from Jeanette, unveiling her long-lasting marital frustration and unfulfilled personal potential. Left on her own, she rediscovers herself as a woman and an independent human being, and lets her confused feelings break out of control. Whatever ensues is the evidence of her emotional turmoil, which cannot be stopped before it turns the fabric of her former life into sizzling ashes.

Casting judgements on the film’s characters might be easy, yet such an approach would go against deep humanity of Dano’s work. For the core value of Wildlife lies in the unconditional trust the director bestows upon his protagonists. Instead of questioning their dubious choices, he carefully listens to their voices, letting them express themselves freely through carefully cast and emotionally intelligent performers. Consequently, he unlocks the story’s affective potential by making it truly relatable.

It is evident that the story carries a very personal significance to the debuting director. Narrating it from Joe’s perspective, he assumes the young protagonist’s stance of empathy and understanding towards both Jeanette and Jerry, laced with hope to “keep things together”. “I remember sort of standing in the middle, feeling the ground shake and not wanting things to tip” – he recalls his own young self in face of his parents’ crumbling marriage. Thus, the figure of Joe, played remarkably by the Australian newcomer Ed Oxenbould, appears as a creative projection of Dano’s own traumatic experience. The young actor’s sensitive presence, imbued with quiet astonishment at the game-changing events unfolding in front of his character’s eyes, perfectly conveys the uneasy position of an unwilling partaker forced into the role of an observer. A caring and respectful son that he is, Joe can do nothing more than silently despair at his mother’s unpredictable actions stemming from her intense urge to fill the emotional void. Not adhering to the current societal norms and adamantly following her self-destructive drive, Carey Mulligan’s mesmerising Jeanette is at once deeply feminine and universal in her extreme vulnerability and neediness blended with an imposing strength concealed beneath a seemingly agreeable facade. By contrast, Gyllenhaal’s outwardly explosive Jerry consistently reveals his gentle, unprotected core.

Successful at completing and effectively guiding his stellar and highly dedicated cast, Dano has nonetheless managed to avoid the common actor-turned-director’s pitfall of creating a performance-based film, proving capable of using the medium’s specificity to his benefit with support of his talented cinematographer, Diego Garcia. So far known mostly for a range of low-key, arthouse productions, Dano’s DP effectively translates the characters’ turbulent emotional world into the language of film through sensitive use of natural light and careful balancing of intimate interior shots with open landscape perspective. Garcia’s attempts to express human sentiments of self-induced oppression and the need to break free with disquieting imagery of wildlife going through its eternal cycles of annihilation and renovation are greatly aided by the composer David Lang. Renowned for the soundtrack for Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth (featuring Dano in one of the leading parts) and a significant musical contribution to the Italian director’s masterpiece The Great Beauty, he brings into Wildlife the subtlety of ethereal, classical compositions flawlessly conveying a profusion of violent emotions simmering under the surface of matter.

The analogy between the natural world and the insurmountable power of human spirit, so effectively inscribed in the film’s tissue, brings to mind Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows and its extraordinary remake by Todd Haynes, Far From Heaven. The Master, a flawed but nonetheless impressive work of Dano’s artistic mentor, Paul Thomas Anderson, has been frequently name-checked by the film’s creators as another significant source of inspiration, next to Hirokazu Koreeda’s body of work, which, in turn, points to the magnificent cinematic legacy of Yasujiro Ozu. Revealing his deep admiration for the Japanese masters, Garcia’s inquisitive and omnipresent camera blatantly stares into characters’ faces in desperate search for emotional truth, while not even for a moment losing sight of surrounding textures and colours.

However, perhaps even more importantly, if somewhat less obviously, Wildlife’s aesthetic draws from the filmic universe of Kelly Reichardt, acclaimed for her slow-paced, reflective and intimate, yet, nonetheless, immensely cinematic pictures, such as Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy or, more recently, Night Moves and Certain Women. Unsurprisingly, Dano contributed to her work as well, showcasing his superb acting skills in Meek’s Cutoff. Reichardt’s northern soul, luxuriating in deep forest greens and snowy expanses, takes an avid interest in the intricacies of human relationships developing on the crossroads of civilisation and the rough, natural world. Her influence is almost palpably present in Dano’s debut, where the landscape and human feelings are just as tightly interwoven as they are in her films, forming a relatively simple, yet intriguing tapestry.

Wildlife’s emotional impact increases gradually, reaching its full potential only at the very end. The final scene in which Joe poses his parents for a family shot, in his desperate attempt to stop time in its tracks (or perhaps even revert its course) by preserving traces of his now foregone childhood on a photo membrane, has a tremendous power of cinematic radiation. Notwithstanding the boy’s hopes to prevent ultimate dissolution of his childish illusion, Jeanette’s and Jake’s disfigured smiles and mutually avoidant, teary eyes point to the fresh lesion which, if given a chance to heal, will surely leave an indelible scar. Just as the nature dies and renovates itself through violent, all-consuming phenomena, in the human world purification occurs in consequence of a sudden emotional outburst. The raw nerve exposed in the process keeps throbbing until it gets covered with a new tissue, which, in some cases, may never occur.

Deeply poignant and intelligent, Wildlife demonstrates Paul Dano’s ability to both convey and stir feelings. It is a quietly potent film, vibrating with an immense force akin to the power of obscured, yet irrepressible sentiments and the vigour of a blaze raising from a spark to engulf the forest. Those unable to sense it tend to dismiss the picture as an overblown portrayal of middle-age crisis. It does, indeed, take some maturity to notice that life is considerably more complex than such a label would suggest, and Dano, however young, is acutely aware of its intricacies. A high degree of emotional and aesthetic sensitivity he has displayed as a debuting director incites curiosity and sharpens appetites for what is to come next. There is a lot to hope for and, judging by the look of things so far, it may be worth the wait.

©Anna Bajor, Tracks & Frames, 2018

English

English polski

polski português

português