It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that the British Film Institute is London’s temple of cinema. Its vast archives satisfy even the most refined tastes. If you happen not to have any evening plans and are incessantly curious about other people’s dreams preserved on celluloid, just browse the BFI‘s listings. Be it a spaghetti western, a kung fu movie with Bruce Lee or a noir classic, it is almost certain you are in for a treat. To make things even more exciting, the Institute runs seasonal programmes dedicated to particular subjects, directors, genres or regions of the world. In September and October, to my unconfined happiness, it celebrated the oeuvre of the independent film guru, Jim Jarmusch. Having kept a safe distance from the Hollywood circles for over 30 years now, Jarmusch is a true self-made man. Fiercely nonconformist and unconventional in his approach towards filmmaking, he has built his own brand, somehow achieved the seemingly unattainable goal of reaching international audiences, and consequently became a guiding light to independent cinematographers throughout the world.

Born and raised in Ohio, after graduating from high school in 1971 Jarmusch moved to Chicago to study journalism at Medill School of Jornalism. It wasn’t long, though, before he felt disappointed with his choice and decided to transfer to the English and American Literature course at the Columbia University, where he honed his creative writing skills. During the final year, he was sent for an exchange programme to Paris. It was meant to be just a six-month stay, but Jarmusch ended up extending it to ten months. Working as a driver for an art gallery, the future filmmaker was spending all his free time in Cinemáthèque Française. It was then that he fell in love with Japanese cinema, watching films by such directors as Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi and Shohei Imamura. Enchanted with the new language he had just discovered, upon his return to the States he applied to the Graduate Film School of New York University and, despite his modest portfolio, was readily accepted.

Studying in New York in the late 70s, Jarmusch found himself in the midst of a cultural revolution. The punk ethos of DIY and anti-commercialism originated in the world of music started to influence other forms of artistic creativity, including film. As a result, the No Wave movement was born. Coined as a satirical wordplay, the term referred to the NY-specific countercultural phenomenon based on rejection of New Wave, that is the increasingly popular electronica-infused variety of punk typified by such bands as Talking Heads and Blondie. But over time, journalists started using “punk” and “new wave” tags interchangeably, causing a terminological chaos and completely blurring the origins of No Wave. Finally, the label post-punk entered the game in order to distinguish the more edgy and raw punk-inspired sound from poppy and heavily synthesised products of Television and their ilk. The same happened on the ground of cinema, where No Wave began designating the unvarnished style of filmmaking which placed mood and feel above structural coherence.

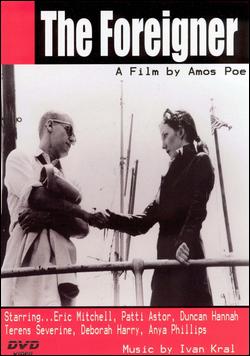

The character and its role in the narrative, an issue treated with contempt by the generation of structuralists, turned out to be of primary concern to the group of directors commonly regarded as No-Wavers. Especially influential among them was Amos Poe, whose early picture The Foreigner (1978) portrays struggles of a European secret agent who arrives in New York expecting further instructions from his contacts. The contacts, however, fail and he is left on his own. Clash of cultures, allure of a big city, sentiment of being lost, chance encounters – the movie contains virtually all elements of Jarmusch’s future cinematic world. The Foreigner‘s story line is sketchy, and the action, at least in the Hollywood meaning of the word, virtually inexistent, except maybe for the final scene of chase. What matters is not what is going to happen next, but what is happening here and now, as far as it concerns the emotional state of the protagonist.

And this is precisely the approach present already in the first Jarmusch’s film, Permanent Vacation. The 16 year-old Allie wanders through the oneiric downtown New York, reading De Lautreamont‘s poetry, visiting his mother in a psychiatric hospital and meeting on his path the city’s odd characters. Not having any purpose or aim, he is drifting in the space and time continuum. And yet, with almost nothing of importance happening on screen, the picture has an absolutely entrancing quality. That’s because it is made with a true notion of style. Permanent Vacation reveals not only Jarmusch’s eye for elegantly balanced bleak compositions, but also his fascinations with all sorts of misfits and outsiders. Besides, it is a wonderful demonstration of the director’s passion for music. Not everyone knows that the film’s score mostly comprises of gamelan sound electronically modified by the director himself. And who could ever forget the scene of Allie dancing to Earl Bostic’s bop piece “Up There in Orbit”? Furthermore, Permanent Vacation marks the beginning of collaboration with John Lurie, the underground saxophonist and founder of The Lounge Lizards, who, having appeared as a street musician in Jarmusch’s directorial debut, went on to compose soundtrack to his next three movies and played lead roles in two of them.

In Stranger Than Paradise, with Lurie in the part of Willie, a Hungarian immigrant ashamed of his roots, Jarmusch’s unique approach towards the character comes into full view. As it was already noticeable in Permanent Vacation, the director is far from judging his protagonists, who are typically very human in their imperfect attitudes. Instead, he looks at them with a deep sympathy and a warm, slightly ironic smile. His sense of humour – wry yet kind-hearted – starts becoming a clearly discernible element of his aesthetic.

As an outsider himself, Jarmusch has always had a soft spot for the strange, unadapted or somehow unfitting. Given that many of his films were made out of the US and/or with foreign funds, they can’t be seriously called American, and even less so, if we take into consideration the director’s ambivalent attitude towards his country of birth. This explains why foreigners are the director’s most favourite leads.

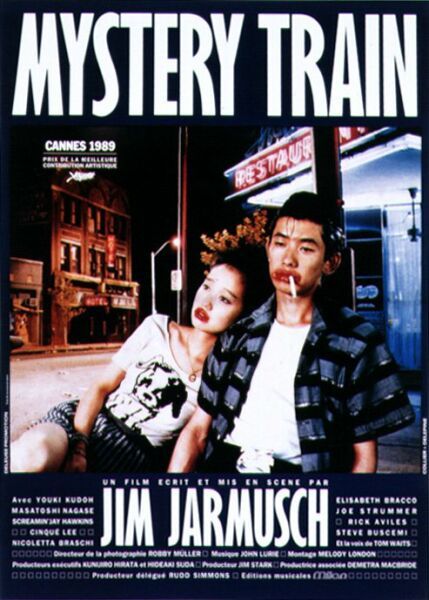

Eva from Stranger Than Paradise, Roberto from Down by Law, the Japanese couple and the Italian widow from Mistery Train, Helmut from Night on Earth and William Blake from Dead Man are all strangers in the world of self-assured natives. Jarmusch makes encounter in the unknown territory the main subject of his films, picturing humans as conflicted creatures who all at once long for a contact with others and feel an urging need to raise boundaries.

Hostility towards a stranger takes most violent forms in Dead Man whose protagonist is a decidedly unwelcome guest in the frontier company town named Machine. Educated and well-mannered, he doesn’t stand a chance in confrontation with the primitive local mentality. Characterised by a well structured script with a dynamic plot firmly advancing towards the solution, Dead Man is one of Jarmusch’s most traditional films in terms of narrative composition. It is also his first experiment with genre resulting in an excellent western pastiche. Poetic and symbolic yet rich in intelligent humour and eventful action, it was bound to achieve a classic status. And it did, despite the initial wave of negative reviews produced by the mainstream critics who weren’t prepared to grasp the film’s subtle allusions and indirect observations regarding the American society.

Four years later, the director’s great passion for genre cinema combined with his deeply rooted attraction for the Orient resulted in the gripping crime drama Ghost Dog. The Way of the Samurai. The picture tells the story of a devoted follower of Hagakure who, thankful to the local mobster Louie for having saved his life, considers himself his retainer and works on his orders as a hitman for the Italian mafia. Widely regarded as a homage to Le Samourai by Jean-Pierre Melville starring Alain Delon, Ghost Dog is also heavily indebted to Branded to Kill by Seijun Suzuki, another Japanese director whose work Jarmusch deeply admires.

Jarmusch’s fascination with the gangster world dates back to his last year at the NYU when he worked as an assistant to the renowned film noir director Nicholas Ray, famous for his sympathetic eye towards rebels and criminals. At about the same time, he also developed an interest in John Boorman‘s work, specifically the 1967 Lee Marvin revenge drama Point Blank, which could be seen during the BFI retrospective. As Jarmusch said in an interview, the inspiration for his second-to-last film, The Limits of Control, was drawn mainly from “the novels of Donald Westlake, who wrote under the name of Richard Stark about a professional criminal called Parker. John Boorman’s Point Blank was based on those books, which I love”.

The Limits of Control tells the story of a mysterious hitman who travels across Spain in order to collect essential information necessary to get hold of a prominent and highly protected figure. For this, he relies on a chain of local contacts. And so, the motif of encounter in a foreign territory appears again.

The film’s title, a quote from William Burroughs, refers to the intellectual oppression exerted by dominant social forces. The only power capable of opposing this terror seems to lay in the faculty of imagination. The extensive use of repetitions on various levels of the story perfectly serves the picture’s enigmatic expression. Echoing phrases and musical motifs, as well as the infinite number of structural parallelisms, create a dreamlike quality and increase the tension of the seemingly humdrum action. The film is yet another demonstration of the director’s playful approach to the narrative convention and of his experimental spirit, which is somewhat at odds with the anti-structuralist background he was shaped in as a filmmaker.

It is impossible to talk about Jarmusch’s work without referring to music as an essential element of his aesthetic. Those more acquainted with his artistic biography know that the coolest filmmaker on the planet is also an accomplished musician who in his free time trades his camera for a guitar and acts as frontman of the rock band called SQÜRL. Jarmusch’s fascination with the aural world has been noticeable since the beginning of his career, but Down by Law with the outstanding score by Tom Waits proved it beyond doubt. Five years later, after a collaboration with John Lurie on Mystery Train, came Night on Earth with another beguiling soundtrack by Waits. Finally, 1995 brought Dead Man whose visual presence seems inseparable from the haunting tunes composed by Neil Young. On Ghost Dog, Jarmusch collaborated with RZA (Robert Fitzgerald Diggs), leader of the hip-hop formation Wu-Tang Clan, and on The Limits of Control – with Boris, Japanese experimental metal band. But it is the last Jarmusch’s film, the vampire drama au rebours Only Lovers Left Alive (more detailed analysis here), that sets music in the centre of the artistic vision and celebrates all its cinematic qualities. The soundtrack by the Dutch, Brooklyn-based lutist Josef Van Wissem is unequalled in its ephemeral beauty and depth which conveys all that the image alone cannot express. Complemented with SQÜRL’s shredding guitars and the otherworldly voice of the Lebanese singer Yasmine Hamdan, Van Wissem’s work becomes an ode to the forgotten spirit of art which, in the modern, technology-dominated world, lives – like Jarmusch characters – on the outskirts of society, marginalised and understood only by a few.

A true maverick of contemporary cinema, Jarmusch doesn’t compromise his ideals in hopes for a popular acclaim. That said, his idiosyncratic aesthetic taste and vision of the world happen to be appreciated by a relatively small but extremely dedicated audience which, not without a reason, seems more numerous in Europe than in the director’s native America. Jarmusch’s slow paced movies, sprinkled with the characteristically dark, deadpan humour and focused on mood and character rather than action, appeal to those longing for intelligent yet unpretentious filmmaking which brings an invaluable reflection on the human condition in the ever so inhuman world. What is more, the unique aesthetic quality of his work inspired and continues inspiring numerous filmmakers throughout the world, including such accomplished directors as Richard Linklater. For Jim Jarmusch is one of a kind. There is something in his films that escapes all attempts of classification. An intangible vibe, a subtle flavour which marks a true artistic personality whose existence makes the world a better place to be.

©AB, Tracks & Frames, 2014

English

English polski

polski português

português